The Bletchley Girls, a recent BBC Radio 4 programme about the women who worked at Bletchley Park during World War 2, had a particular resonance with me. In 1987 my parents moved to a small West Dorset village, and their next door neighbours-but-one were a lovely brother and sister, Cecil Gould and Jocelyne Stacey, who lived together in what I think had been the old school house: Jocelyne had the upstairs flat and Cecil the downstairs one, which included the huge impressive schoolroom or hall which he had converted into his library. Cecil had been a former Keeper and Deputy Director of the National Gallery in London, and so unsurprisingly had a huge collection of books.

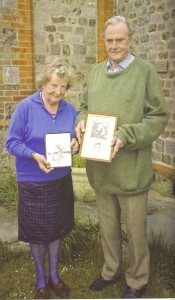

Jocelyne Stacey and Cecil Gould outside their home, 1993. Photograph by Jonathan Betts, reproduced in his fantastic 2006 book on Rupert Gould.

Their father, Commander Rupert Gould, was an extraordinary man: a science educator and Brains Trust panellist, umpire at Wimbledon, and researcher into the Loch Ness Monster. But he is perhaps best known for being the man who restored John Harrison‘s marine chronometers.

Jocelyne was a wonderful character, full of fun and mischief. Chap and I always went and had coffee with her when we visited my parents, and enjoyed a natter and a giggle. It was during one of these visits that she told us that she had served at Bletchley Park during the war: she was just about to travel to the United States to give some talks about her experiences. I was fascinated, but this is my eternal regret: I didn’t ask too many questions about her time there. This was in the late 80s, before Bletchley had really impinged on our collective consciousness as a nation, and the conversation moved on and I never steered her back to the subject. The work of all who had worked at Bletchley Park was covered by the Official Secrets Act, and many still honoured their vow of silence, all those years on, even though we were clearly in a time when it was no longer a matter of national security.

Sadly neither Jocelyne nor Cecil are still with us, and I never talked in depth with Jocelyne about her wartime experiences. I wish I had done so, and recorded her reminiscences. She died in 2001.

All I can find out now about her experiences are from the Bletchley Park website Roll of Honour: she worked at Bletchley from 1942, she was with the WAAF, where she was a Leading Aircraftwoman (LACW), and she worked in the Air Section. This section was responsible for decrypting non-Enigma signals from German, Italian and Japanese Air Forces, and produced intelligence reports. Cecil also worked in intelligence, for RAF Intelligence, during the war.

Thank-you, Jocelyne, and thank-you, Cecil.

I can’t recommend enough Jonathan Betts‘ 2006 book about Rupert Gould, Time Restored: The Harrison timekeepers and R.T. Gould, the man who knew (almost) everything. And of course there is Dava Sobel‘s cracking 1995 book Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time.